Bladee And Mechatok Are Winning And Losing At The Same Time

By Eli Enis

Bladee and Mechatok like to think of luck as a paradox. The 26-year-old cloud-rap icon and the 23-year-old producer are sitting in a Swedish hotel room talking about how their new album documents their simultaneous failure and success at creating perfect pop music. The eight-track project is simply titled Good Luck, but they don’t subscribe to the idiom’s optimistic connotations. “When you say ‘good luck’ to someone, you’re kind of implying that there’s a good chance that it might not work out,” Mechatok says with a smile. “You’re not saying that, if you’re confident, it’s going to be fine.”

At the very least, the album’s existence is the result of some good fortune. The two artists met a few years back through a mutual connection in the London club scene. The Berlin-based Mechatok, real name Timur Tokdemir, was an auxiliary member of the dynamic Bala Club electronic music collective, which cross-pollinated the ethereal rap movement that Bladee, born Benjamin Reichwald, and Yung Lean were spearheading in Stockholm. As they tell it, it was only a matter of time before they worked on a project together, and when it finally happened, their chemistry was extremely intuitive.

”We quickly discovered that we have the same habits where, if you hang out, you either listen or make music,” Tokdemir says.

Despite emerging as a distinctly internet-based artist and developing his career in the early days of SoundCloud, Reichwald is a uniquely private and elusive figure for a rapper of his generation. Until last year, he refused to do interviews; his lyrics have never revealed much about the man behind the misty, celestial delivery. His social media pages mostly consist of arcane images with esoteric captions. While speaking with MTV News via video chat, he’s about as soft-spoken and reserved as he sounds when he’s performing, but his decision to share more about himself with his fans aligns with his shift toward making more accessible music.

Since forming the Drain Gang artistic collective in 2013 with rappers Thaiboy Digital and Ecco2k and producers Whitearmor and Yung Sherman, Reichwald has fostered a cultish following of international listeners who devour anything he puts his name on. The dreamweaving production, fairy-dusted Auto-Tune, and short, simplistic song structures of his 2018 records, Red Light and Icedancer, have become sacred texts for the emerging wave of hyperpop artists led by Glaive, David Shawty, and Ericdoa. Even if his earlier projects weren’t direct influences, Bladee’s melancholy spaciness can be heard in Post Malone’s 2015 breakout “White Iverson,” and his sound feels spiritually in tune with the extraterrestrial psychedelia of American rappers like Lil Uzi Vert, Playboi Carti, and the late emo-rap pioneer Lil Peep.

Unlike the other artists who propelled themselves out of the SoundCloud trenches to attain major label deals and sponsorships, Reichwald has always remained in the periphery. All of his projects have been released on the Stockholm indie label YEAR0001, he’s rarely collaborated with anyone outside of his Drain Gang cohort. Despite the considerable popularity of his labelmate Yung Lean, his monthly listeners on Spotify alone amount to little more than half that of his longtime collaborator. To him, that’s perfectly fine, and he thinks it correlates with his personal philosophy as of late: a rejection of materialism in favor of universalism, a pivot from two years back when he was doling out tag-poppin’ flexes on Red Light’s “Steve Jobs.”

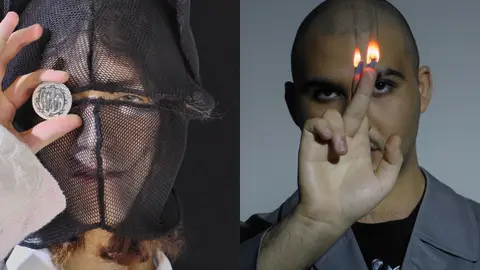

Benjamin Reichwald, a.k.a. Bladee

After spending two years in London and another in Berlin, Reichwald moved back to Stockholm at the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic and has since released two other albums. April’s Exeter featured the most docile vocal delivery he’s ever employed over plush instrumentals that channel the coziness of the Sleepytime tea bear. July’s 333 was more akin to the transcendental hip-hop of his older material, but both albums contain some of the catchiest songs in his whole catalog.

“Looking at Exeter and this project [Good Luck], I wanted to make something more approachable in a way,” Reichwald says. “But also I always want to make it more true to my expression.”

Tokdemir says he’s always heard a “curiosity” for something grander in Reichwald’s melodies, and on Good Luck, the producer’s sweaty club instrumentals allowed the rapper’s icy cadences to thaw into warm, steamy pop hooks. Songs like the Italo-disco banger “Rainbow” and the techno-thumping “God” are the type of light-show EDM you could imagine thousands of people jumping to at Tomorrowland. Even the rap-based track “Drama” has a sexy buoyancy far more upbeat and punctuated than the lowercase sadness of Bladee’s 2018 album Icedancer.

“It’s not like a Britney Spears album,” Tokdemir says while mentioning the hymnal ambient songs that bookend the record. And he’s right. As accessible as the songs are compared to some of Bladee’s other albums, it’s unlikely that any of these tracks will scrape the Billboard Hot 100. However, the fact that they’re pop songs that could have been taken to that level is what Reichwald and Tokdemir find so interesting about them.

Timur Tokdemir, a.k.a. Mechatok

”We’re trying to make these pop songs but also we’re not managing to,” Tokdemir explains. ”It’s more about the tragedy of trying to make the pop song than the pop song itself. And then, of course, in a bigger way, it’s more so the tragedy of trying to make it and [the dualities] of winning and losing at the same time.”

That idea seems to almost contrast with the concept of luck, which is predicated on one of two results — you either win or lose; you’re either lucky or unlucky. Tokdemir and Reichwald think there’s more nuance to the concept. “There is no winning,” Tokdemir says. “Even if you become a millionaire, you’re probably going to have some other problems.”

“[Luck] is a metaphysical thing that doesn’t exist,” Reichwald adds. “But everyone speaks of luck and can feel lucky.”

In that sense, the album is more about the mechanic of luck than the success of a given pop song. That dualistic theme is visually represented on the album’s artwork, which features a coin with a demon on one side and two angels high-fiving on the other. In promotional video graphics, the coin is seen spinning, a symbol that the record lives in the limbo between heads and tails. Following that meta-narrative to its logical conclusion, Reichwald feels the interstitial zone between winning and losing is a reflection of where he’s at in his career.

“I’m happy with where I’m at even if I’m not the most successful, or whatever,” Reichwald says with thoughtful consideration. “I feel like I haven’t compromised and done stuff I wouldn’t be comfortable with. So I’m happy with where I’m at.”

On Good Luck, Reichwald freestyled almost all of his lyrics in the studio, and those careerist reflections came swimming out of his subconscious. On “Rainbow,” he sings the phrase, “I could have had it all / I didn’t wanna have it,” which articulates his resistance to sacrificing an iota of his artistic integrity, and a conscious choice to remain in that spinning limbo.

“To strive for something is, for me, the most beautiful thing, rather than to achieve something,” Reichwald says. “Because then you’re at this place when you have nothing.”

The other themes that are sprinkled throughout the record — love, loneliness, oneness — can all be interpreted through the lens of luck and its inherent dichotomies. On the muted club track “Sun,” Reichwald sings, “Not a fault / Not a wrong / Nothing’s off,” which is his way of challenging ideas of right, wrong, lucky, and unlucky with a commitment to the eternal in-between. During the chorus of “Rainbow,” Reichwald asks the simple question, “Do you believe in love?,” which sounds like a parallel to asking “Do you believe in luck?”

”To me, all of this stuff is still the same coin-spinning kind of mechanic,” Tokdemir says. “It’s not about saying the one thing or the other thing, it’s about portraying the tension of these ways of seeing it. It’s more the relation of two things than it is the one or the other.”