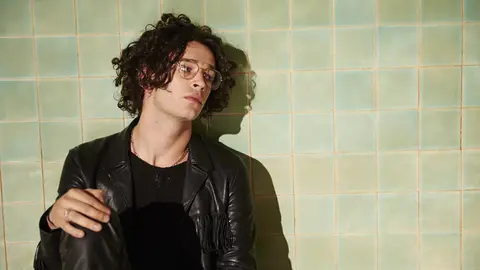

Cover Story: The 1975

Photography by: Will Crakes

Video by: Nate Ford

A haunted subterranean pool in Milwaukee is the exact sort of narrative flourish you'd expect to find in the lyrics of a song by The 1975, and here we are, trying to make sure frontman Matty Healy doesn’t sit on a pool chair that belongs to a ghost. The Rave, where the British band is playing tonight, used to be a lodge for the local Fraternal Order of Eagles, and supposedly someone drowned in its now-empty pool many years ago. Lore has it that musicians booked at the cavernous venue upstairs have had their whole sets fucked up after sitting in the ghost chair. Unfortunately, Healy and I are unsure which chair is which, and neither of us is trying to play games with the Wisconsin spirit realm today. So the band’s equally beloved and divisive 26-year-old leader decided to split a pack of cigarettes with me on the floor of the dusty pool deck. In leather pants, obviously.

The 1975 confuse people. Since the release this February of their latest album, I like it when you sleep, for you are so beautiful yet so unaware of it (and yes, we’ll get to that title), I’ve been trying to pin down what I like so much about Healy’s band — that’s him at the helm, Ross MacDonald on bass, Adam Hann playing lead guitar, and drummer George Daniel. Their self-titled full-length debut immediately hit No. 1 on the U.K. albums chart in 2013. That summer, they opened for the Rolling Stones, where they were regularly heckled by the Stones' fans; the next year, the NME Awards voted them “Worst Band,” clinching that victory over One Direction and Imagine Dragons. The band’s American audience has exploded this year, sending their shows from mid-level indie venues to sold-out arenas in the span of a few months, doing nothing to quell the raging debate about what it all means. “We’re the biggest band in the world that nobody’s ever heard of,” Healy explains, half-joking.

Like them or not, The 1975 are a real band, not a focus-grouped X Factor creation. By the time snobby adults and British media were sniffing at them, they'd already been playing together for a decade. Having met in 2002 at Wilmslow High School, just south of Manchester, England, the four got their start playing covers at increasingly turnt underage punk shows. Between writing their first original song and releasing their first EP as The 1975 in 2012, they’d cycled through six name changes — past handles included Drive Like I Do, B I G S L E E P, and the abjectly terrible Forever Enjoying Sex — before finding inspiration scrawled in the back of a used volume of Kerouac poetry that Healy picked up in Majorca, as one does: “1 June, The 1975.” A string of four EPs between 2012 and 2013 solidified the band’s cult following and sharpened their pop writing skills to glistening precision. It wasn't that they’d found their lane so much as realized how to effectively swerve between all of them. Flashes of perfect '80s-inspired pop-rock were bookended by wordless ambient experiments. None of this could have entirely predicted the dense, uncategorizable glory of their latest record, but at least they tried to warn us.

I’ve never heard a 1975 song on American radio, but that night in Milwaukee, a legion of teens were wrapped around the block behind the Rave, camping in 80-degree heat under a giant sign: “No Lining Up Til 7AM Tuesday.” “They’ve been here since Sunday night,” the building manager had told me earlier. “I tried to tell them to go away. They don’t care.”

The fastest shortcut to understanding The 1975 is understanding what people don’t like about them. Ambivalent reviews of their latest album do not exist, which may or may not shock you given its title alone, which would never work if it weren’t sprawled in neon across this year’s most intriguing, ambitious pop record. There’s no way any of this would work —— the plunge into shameless ‘80s supermarket funk, the run-on neuroticism, the lyrical nods to the '60s Situationist manifesto Society of the Spectacle astride musings on Kardashian banality, the fact that there is a song titled “Please Be Naked,” and so on — if the music weren’t fucking good, and if Healy didn’t sing it like he meant it. But the music is, and Healy really fucking does.

“Everything that we do could be perceived as pretentious," Healy says, dragging off a borrowed menthol. "Usually it’s just used as a vehicle to talk about what people don’t like about me, isn’t it?” He gets it — he hasn’t exactly gone out of his way to counter his public perception as a rock star who can’t keep his opinions to himself. In person, though, his only cliché is his head-to-toe black leather. “I suppose this record is very much an odyssey into my brain," Healy adds. "But what I don’t do is patronize our fans — or let’s just say people. I don’t ask for permission, and I give people the benefit of the doubt. Because people are smart. Stupid people are stupid, but there’s enough smart people in the world. I like the divisiveness of my band, to be honest with you. The idea of provoking ambivalence in somebody really scares me.”

Part of The 1975’s mystique is that nobody knows where to put them. Are they a boy band? An “alternative rock” band? And if so, “alternative” to what? Certainly they exist parallel, or maybe perpendicular, to the Big Pop cosmos: Healy was recruited to help pen a song for One Direction’s Four, though it didn’t end well. (Cue Healy licking a cardboard cutout of Harry Styles in the brilliantly tongue-in-cheek “Love Me” video.) There was a Taylor Swift Thing, and a Bieber Thing. But The 1975 don’t fit in that world, either, at least according to Healy. “Those things” — by which he means Bieber things — “are comprised of big cultural movements we’re not really part of,” he assures me. “I can’t be that objective about it, because I’m me, but I don’t feel that famous. I think people get confused about how famous they are because they live on tour and every time they go outside, they’re surrounded by people. It’s like, you did tell those people you were gonna be there…”

Calling The 1975 a boy band, as many do, means you’ve astutely noted that the band is made up of four twentysomething “boys.” Not that Healy balks at the term. But with all due reverence for the boy bands I grew up worshipping, I don’t remember JC Chasez riffing on cocaine psychosis, or 98 Degrees fucking up the game with six and a half minutes of ambient house when the mood struck. Still, most rock bands don’t sound like this, either, and The 1975 don’t really want to be a rock band anyway. “People call us a guitar band. You might as well call us a microphone band,” Healy says. “By the time we even [called ourselves The 1975], we’d been a band for eight years, left that, and started making really left-field, European house music. And our involvement in that is where The 1975 is founded: Oh fuck, if we take it back to being a band — four people, clean lines, silhouettes — and we sound like no other band, that’ll work, right? Certain people couldn’t see past it, but it was the right thing to do. Because everybody was a bedroom artist at the time, and everybody had a laptop—no, we’re gonna be a fucking big band that appeals to people who actually like music.”

"I’m not going to apologize for embracing this intense emotional investment that I get from people. Because it’s a big deal."

Surely 1975 cynics should be able to look past the band’s surface aesthetics and deduce that whatever this may be, it isn’t the Sixth Second of Summer just because Healy likes to perform with his shirt off. Really, though, aesthetics have nothing to do with the doubt that drives The 1975's most vocal critics: How good could a band be if they play to a sold-out room of screaming teenage girls every night?

I kept reading about the band’s massive teen girl fandom — stated most dramatically in reviews written by adult men — before I went to my first 1975 show last month in Brooklyn at a packed Barclays Center. These are girls who present Healy with handwritten letters and philosophical textbooks and used razors so they can’t cut themselves anymore, all of which he keeps stored in suitcases. And those girls were all there at Barclays, with their best friends and some of their parents, screaming the loudest and hugging each other the hardest and easily having the best time of anyone in the arena. But there were also no small number of twentysomething men and women in their work clothes and college kids getting crazy on a weeknight, singing every word. “Bitchhhh, I’ve had two and a half beers and I have school tomorrow!” a college-aged woman behind me shouted ecstatically as the opening riff of “Love Me” hit.

There was a weird sense of togetherness in the room through The 1975's 90-minute set, like 10,000 strangers and I had just been entrusted with a secret — one that involved a sax soloist and Turrell-inspired, pink-washed LED installations and the most poignant ballad about Instagramming a photo of a salad that should ever be allowed to exist. I didn’t see one person duck to the exit before the four-song encore, for which the band brought out a six-piece gospel choir to help them with “If I Believe You,” a crushing spiritual about atheist crisis. Walking to the train later, I overheard a cardigan-wearing dad muse to his two teenage daughters in disbelief: “The guy with the hair could really play guitar! I kinda thought they were good.”

“Listen.” Healy tends to talk like his mouth is racing to keep up with his brain, but when our chat by the haunted pool turns to his fan base, he speaks with steady conviction, stating what should really be obvious. “Anybody of any kind of intellect understands that the most active people as consumers of music are young women. The most active people on social media, when you come to talking about music, are young women. Mary Shelley wrote Frankenstein when she was 18, do you know what I mean? There’s fans of ours that I meet that are far smarter than me. Of course they scream and they go wild — but if I was young and really, really excited, and drunk, and my favorite band was there, I’d be screaming and going wild!”

He's fired up now. “And you know, I could be really, really concerned and want to appeal to the kind of crusty, liberal, North Londoner [audience]. But trust me. I’m telling you as a grown-up person: If you do what I do every single night, and you get the choice to play to that group of people or a bunch of screaming, younger girls who fucking love you, you’re going to choose that one. Because it means more. It means something to those people. And I’m not going to apologize for embracing this intense emotional investment that I get from people. Because — Because it’s a big deal.”

Falling asleep the other night, I put on a reality show I found in an internet rabbit hole called Rock This Boat: New Kids On The Block. You can probably guess what it’s about: Currently in its second season, the show documents the seventh annual NKOTB cruise, where the reunited gang drink Mai Tais and take tyrannically regulated selfies with 3,000 of their now-middle-aged fans, all but a handful of them women. Sure, maybe there’s a whiff of desperation to the whole enterprise, but at least this much is clear: Decades later, these women still hold on to the emotional investment they made in this band, and very much vice versa. Requisite douchery aside, it’s actually kind of sweet.

In other words, it’s not like The 1975 are the first group of dudes to forge meaningful, enduring relationships with their young, female audience. But by my second time experiencing their live show, I start to think they are the first to do it with this degree of trust and mutual respect. It’s not so much that Healy & Co. challenge their fans; they assume without question that their fans are up to a challenge, that there is nothing too esoteric to unite an arena full of teenage girls and dads and jaded music writers, as long as you do it with conviction. With When you sleep, the band is granting its fans permission to get comfortable outside what the pop charts deem appropriate (read: marketable) for 13-to-19-year-old girls. “I think in making this record, I gave myself license to know that I had the benefit of the doubt from our fans,” says Healy. “I could be really specific because they know me, and that’s what they want. They don’t want me singing fuckin’, you know, ‘Moves Like Jagger.’”

“One of the things that I love about The 1975 is now I’ve realized that we’re kind of this gateway band,” he goes on. “Gateway bands used to exist, but they were normally shitty — you know, bands that straddled between the truly alternative scene and the mainstream market. A soft, easy band for the kids to transition from the Backstreet Boys to fuckin’ Cannibal Corpse or whatever it may be. With us, of course we’re gonna get a lot of kids who were into, I don’t know, 5 Seconds of Summer. And then they get inside and they realize: I can stay here. I can grow with this band. This isn’t a faddy thing. This isn’t the Backstreet Boys. You’re not being told to like us.”

Let’s clear something up before we go further: “Intelligent pop,” as a concept, kind of sucks. It’s one of those anti-genres built around what they aren’t; in this case, it’s the assumption that regular pop music is for mindless drones. And it’s not a stretch to see how Healy’s lyrics, at their iffiest, could read as pretentious; shit, some of them are pretentious. (“I know that maybe I’m too skeptical / Even Guy Debord needed spectacles / You see, I’m the Greek economy of cashing intellectual cheques,” from the half-rapped folktronica ditty “Loving Someone,” is A Lot.) But when you see the emotional response these songs get — not on the internet, in real life—you know that’s not what this is. The 1975 don’t care about subverting pop as a form; they want to make pop they believe in.

“The reason we reference the ‘80s so much, it’s not because of particular bands or particular songs,” Healy explains. “It’s because it was a time when pop music wasn’t so encumbered with self-awareness and fear and cynicism. I wasn’t there — ‘grunge killed pop,’ I don’t know what happened. But I know that pop music existed where [there were] records like So by Peter Gabriel and Tango in the Night by Fleetwood Mac — amazing records that could almost be considered as supermarket favorites, but also really credible, forward-thinking pieces of work. That doesn’t really exist as much anymore. Pop music now, if it’s massive on the charts, is tarnished with a lack of credibility, or a sense of that. Because, fair enough, there’s a lot of shit, and people don’t know what they’re allowed to like. It’s really difficult to see in pop music what’s a genuine expression and what’s just something that’s a commercial statement. The thing with pop music, with me, the only question I allow myself is: Well, do you believe it?”

"The past is a kind of fuzzy memory, and the future is a kind of vague uncertainty."

There’s this line on “Love Me” that’s been stuck in my head since I first heard it. Healy sings in his best Bowie voice: “I’m just with my friends online, and there’s things we’d like to change.” At first the line made me laugh; something so ridiculously mundane had to come with a wink. After a few listens, it began to embarrass me. It felt way too close to be presented at an ironic arm’s length. I could no longer tell if the line was gently mocking the performative digital existence of an entire generation, or wryly indicting the author himself, or totally sincere, or just some shit Healy wrote in his diary when he was high that sounded cool. Mostly I couldn’t tell if I hated it or if I was it. I start to ask him about it, then decide I don’t really want to know for sure.

Healy often talks about wanting to be an ambassador for, as he puts it, “the generation that creates in the way that we consume,” which mostly refers to his equal love for Tool and Marvin Gaye but also means he thinks about the internet a lot. The band became obsessed with the idea of cultivating enigma in an era governed by accessibility; if the inscrutability of a Michael Jackson or a Morrissey has been critically endangered by a culture where your favorite celebrity just told their 10 million followers that they’re loving the results of their new detox tea, how do we get that feeling back?

So last year, The 1975 disappeared. (Yes, a year before Radiohead did.) It was a weird time for the band; after a grueling year of touring their first record, Healy was having something of an existential crisis, and the coke habit wasn’t helping. With no explanation, Healy posted a Situationist-style cartoon. “Hey! This is the era of reflection right?” it read. “We’ve killed the rockstars. Just another casualty in the war against popular art — butchered by our postmodern reflective propensities and selfie awareness. Our projected identity needs to change not only visually but philosophically — how do you do that? Firstly we must reclaim our identity and repossess our control of it.” It ends: “We are already gone.” Overnight, the band’s social media accounts had been deleted, as had those of its individual members. The story blew up: Are The 1975 Quitting Music? Fans were distraught. A day later, The 1975 had returned to announce their strange new album, When you sleep.

“So me and [the band’s manager] Jamie were talking about how we fuck around with the internet, because the internet’s boring,” Healy says when I ask gently if it was all a stunt. “And do we want to be a band that puts up a picture of their album, and then everyone goes, 'Hey, did you see The 1975 put out a new record? Oh, cool, yeah, cool' — and then it’s over within 10 hours. Or do we go back to our idea of desire being far more potent than obtaining something? Afterwards I was a bit like, Oh, fuck, I’ve played with these kids a little bit. But remember, I’d also been out of The 1975 for six months making the record in the studio. I hadn’t been on Tumblr and Twitter and I wasn’t thinking about it. So I just thought, Well, yeah, delete it, it’ll be wicked! Just fuckin’ delete it.”

So they deleted it. Some people thought it was clever; some thought it was a dick move. “I thought it was just a thing,” Healy explains. “It was me turning Twitter off on my phone for 24 hours, and thinking Oh, that feels quite nice, and turning it back on.”

I ask if turning it back on felt good.

“Not really,” Healy says quietly, then counters himself without skipping a beat. “But I mean, that’s not true. You can’t pretend that things don’t exist.”

I don’t know how many times I’ve fantasized about deleting it all, but I never actually do, I tell him.

“You remember your pre-internet brain, and you remember doing those things, but you don’t really remember how it felt,” Healy says. “You don’t really remember how time felt. There’s that guy who wrote that book, I can’t remember what it’s called, fuckin’ genius guy. But he’s saying that the world has always been informed by people who read books, and not necessarily academically, but the concept of a narrative is very important to people’s lives. Those people grew up with not necessarily a sense of purpose, but a sense that your life is leading somewhere. That’s the way I relate to my music, because I see The 1975 as this story.”

Healy’s hands fly as he talks, the fringe (yes, fringe) from his sleeves swinging. “But as we go into the future, the world is gonna start being informed by people who didn’t grow up with that narrative — who grew up with more of a sense of immediacy. And we start to feel more like a unit amongst other units, and everything becomes a lot more compartmentalized. So when we talk about Twitter, we know that we were happy before, but we can’t remember how it felt, so we won’t take the risk to leave it. The generation after us now, they don’t have that weird nostalgia or sense that something’s wrong: I didn’t used to do this. I didn’t used to need this.” He lights a fourth cigarette.

“But I think that the way we all live our lives is that there’s a spotlight on now, and the past is a kind of fuzzy memory, and the future is a kind of vague uncertainty,” he continues. “It feels like — because of the ways that things have happened, and there’s been so many opportunities for me to give up, and so many times where I must’ve been deluded—it could only have been a story. Because this is a story. The 1975 is a story. The lyrics are a story. My life is the thing...”

He pauses for a moment, as if just remembering he’s still speaking out loud into a microphone. “Did I answer your question?” I don’t remember what it was.

Later, after Healy and the rest of the band have left for soundcheck, I hear a disembodied wail from downstairs. I follow the sound; it’s coming from the pool room, which usually stays locked. The band’s touring sax player is practicing his solos in the empty pool’s deep end, echoing endlessly across the cavelike space. It's almost too surreal. "Well," I ask myself, "do you believe it?" How could I not?