What's the Big Deal?: Vertigo (1958)

Jimmy Stewart is afraid of heights; there's a bell tower at an old Spanish mission; Kim Novak is blond. These are the famous traits of Alfred Hitchcock's Vertigo. But in many circles, the film is also known as one of the best movies ever made, by Hitchcock or anyone else. Why this one? Of all the greatest films made by the greatest directors, why does Vertigo rank so dizzyingly high? The praise: Vertigo nabbed just two Oscar nominations, for its art direction and sound, and performed modestly with critics and audiences. Its fame came later, when film buffs began to re-evaluate it. It was No. 61 on the American Film Institute's 1997 list of the best movies of all time, and No. 9 on the 2008 revised list. Sight & Sound's once-a-decade poll of top critics had it in fourth place in 1992, second place in 2002, behind Citizen Kane. The context: In many ways, Vertigo was unremarkable. It was Alfred Hitchcock's 46th movie, the fourth one to star James Stewart, and probably the 46th one to feature a blond leading lady. Mystery, intrigue, murder ... yep, typical Hitchcock. Its release in 1958 was nothing special, in part because it came near the end of a decade that had been hugely successful for Hitchcock, with Strangers on a Train, Dial M for Murder, Rear Window, To Catch a Thief, The Man Who Knew Too Much, and a popular TV series. Contemporary reviews said the same thing about Vertigo that many first-time viewers say about it now. "The film's first half is too slow and too long," said Variety in its spoiler-ific review. (Seriously, don't read that review if you don't already know every detail of the plot from start to finish.) The Los Angeles Times said it was "hard to grasp at best, [and] bogs down further in a maze of detail." The New Yorker claimed Hitchcock "has never before indulged in such farfetched nonsense." The New York Times' Bosley Crowther loved it -- "[The film's] secret is so clever, even though it is devilishly far-fetched, that we wouldn't want to risk at all disturbing your inevitable enjoyment of the film" -- but he was in the minority among his peers.  It was only in retrospect that Vertigo came to be seen as Hitchcock's most personal film, considered by many to be his best. It's about a man whose obsession with a woman leads him to make over another woman in her image. Roger Ebert points out that

It was only in retrospect that Vertigo came to be seen as Hitchcock's most personal film, considered by many to be his best. It's about a man whose obsession with a woman leads him to make over another woman in her image. Roger Ebert points out that

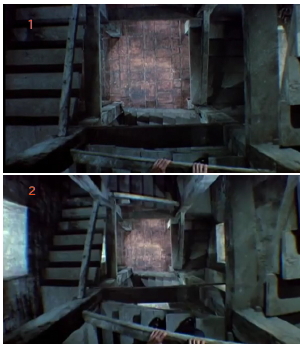

Alfred Hitchcock was known as the most controlling of directors, particularly when it came to women. The female characters in his films reflected the same qualities over and over again: They were blond. They were icy and remote. They were imprisoned in costumes that subtly combined fashion with fetishism. They mesmerized the men, who often had physical or psychological handicaps. Sooner or later, every Hitchcock woman was humiliated.... [Vertigo deals] directly with the themes that controlled his art. It is about how Hitchcock used, feared and tried to control women.Such meta-commentary would have been lost on viewers in 1958, when Hitchcock was seen more as a talented showman than an artist. (Think Spielberg, before Schindler's List.) When a restored version was released theatrically in 1996, Newsweek's David Ansen wrote, "Other Hitch movies were tauter, scarier, more on-the-surface fun. Vertigo needed time for the audience to rise to its darkly rapturous level." He says it's Hitchcock's masterpiece because "no movie plunges us more deeply into the dizzying heart of erotic obsession." Adding to the film's mystique was its unavailability. (Like many Hitchcock protagonists, we want what we cannot have.) It was one of five movies that Hitchcock owned outright, and he removed it from circulation in 1973, having been disappointed by its initial reception. It was rereleased, both theatrically and on home video, a decade later; by then, the people who tell us which films we're supposed to love had decided this was one of them. The movie: Stewart plays John "Scottie" Ferguson, a bachelor who quit the police force after a spell of vertigo led to the death of a fellow officer. He is hired by an old college acquaintance to follow the man's wife, Madeleine (Kim Novak), because he fears she is losing her mind. In the course of stalking her, Scottie comes to fall in love with Madeleine, a scenario that rarely ends well for all involved.What it influenced: The most iconic image from this film is a spiraling series of staircases, one that the acrophobic Scottie cannot hope to ascend. You can bet you'll see this point of view duplicated in any movie whose characters enter a stairwell. (Seems like it's usually an apartment building, and it's cops chasing a bad guy up to the roof.) No director can resist the urge to stand at the bottom and look up, or to stand at the top and look down. It just looks so cool.

But Hitchcock did something else noteworthy in that scene, too, something that has since become a standard filmmaking maneuver and is often called a "vertigo shot." Scottie makes it halfway up the stairwell, then looks down. As he does, the distant floor seems to fall even farther away from him, while his hands on the railing -- in the foreground -- remain constant. This is accomplished by zooming in with the camera lens while simultaneously pulling the camera itself back. Whatever is in the foreground stays the same, while the background gets farther away. This has been duplicated countless times since Vertigo, usually to show that a character is stunned by some new realization or a sudden turn of events. It's used all the time. A YouTube montage of several examples is posted below. The vertigo shot (also called a trombone shot, a stretch shot, or a Hitchcock zoom) was devised by Hitchcock's second-unit director, Irmin Roberts, and came to be identified with Hitch. Quite a few films have paid homage to Vertigo's opening sequence, too, at least in spirit. Scottie sees a man fall to his death from a great height and is thereafter haunted by it. Sometimes this scenario is repeated literally (as in Cliffhanger, which starts with Sylvester Stallone losing his girlfriend in a rock-climbing accident), but usually it's metaphorical. How many movies start with something going tragically wrong and the protagonist -- often a cop or soldier -- blaming himself for it? And how often is that weakness later exploited by the bad guy, who knows his enemy is haunted by the past? We can't claim that Vertigo invented this plot device, but it's certainly been used regularly ever since.In the book A History of Narrative Film, David A. Cook names another way that the film was influential. "Vertigo suggests not only the fraudulence of romantic love, but of the whole Hollywood narrative tradition that underwrites it." The movie's dark ending, "unsatisfying" according to the usual Hollywood storytelling method, was echoed in the French New Wave that came shortly after it. (Not coincidentally, it was the French directors who first took Hitchcock seriously as an artist.)

But Hitchcock did something else noteworthy in that scene, too, something that has since become a standard filmmaking maneuver and is often called a "vertigo shot." Scottie makes it halfway up the stairwell, then looks down. As he does, the distant floor seems to fall even farther away from him, while his hands on the railing -- in the foreground -- remain constant. This is accomplished by zooming in with the camera lens while simultaneously pulling the camera itself back. Whatever is in the foreground stays the same, while the background gets farther away. This has been duplicated countless times since Vertigo, usually to show that a character is stunned by some new realization or a sudden turn of events. It's used all the time. A YouTube montage of several examples is posted below. The vertigo shot (also called a trombone shot, a stretch shot, or a Hitchcock zoom) was devised by Hitchcock's second-unit director, Irmin Roberts, and came to be identified with Hitch. Quite a few films have paid homage to Vertigo's opening sequence, too, at least in spirit. Scottie sees a man fall to his death from a great height and is thereafter haunted by it. Sometimes this scenario is repeated literally (as in Cliffhanger, which starts with Sylvester Stallone losing his girlfriend in a rock-climbing accident), but usually it's metaphorical. How many movies start with something going tragically wrong and the protagonist -- often a cop or soldier -- blaming himself for it? And how often is that weakness later exploited by the bad guy, who knows his enemy is haunted by the past? We can't claim that Vertigo invented this plot device, but it's certainly been used regularly ever since.In the book A History of Narrative Film, David A. Cook names another way that the film was influential. "Vertigo suggests not only the fraudulence of romantic love, but of the whole Hollywood narrative tradition that underwrites it." The movie's dark ending, "unsatisfying" according to the usual Hollywood storytelling method, was echoed in the French New Wave that came shortly after it. (Not coincidentally, it was the French directors who first took Hitchcock seriously as an artist.)What to look for: Hitchcock's first dozen movies were silent, and for the rest of his career he was one of the world's most visual directors. He knew how to tell a story with images rather than words. Sometimes, as with the "vertigo shot," the effect is obvious, and no viewer could miss it. But in other instances he was more subtle. Note, for example, the many shots of Scottie driving down San Francisco's hilly streets, but never up them. This is a man who gets dizzy in high places and who is currently falling in love -- yes, "falling" in love, a useful figure of speech.If it's your first time seeing the film, two questions might come to mind: Where is Madeleine's husband during all this? And what does Scottie's vertigo have to do with it? Both the husband and the vertigo seem so important at the beginning, then fade away until the midpoint. Be patient.Hitchcock blamed the film's commercial failure partly on its star, Jimmy Stewart, being too old (which is lame, since Hitch is the one who cast him). Stewart was 50; Novak was 25. The director may have been right that the age difference was a turnoff, but it makes the film better, as it underscores the desperation and futility of Scottie's pursuit. Never mind the other, larger reasons Scottie can't have Madeleine; here's an obvious one, staring us all in the face. Speaking of underscoring, Bernard Herrmann's music is typically amazing. The opening-credits sequence has an ominous, portentous tone that you almost never hear in movies anymore. For the love theme, Herrmann borrows from the Richard Wagner opera Tristan und Isolde, which is also about love transcending death. (No, I didn't notice that on my own. I was barely aware that there was an opera called Tristan und Isolde, let alone know what it sounds like. It's probable that 1958 audiences were more familiar with famous operas than I am.)Most of the film is told from Scottie's point of view. We don't know anything that he doesn't know. Then, for one scene, the point of view changes and we are given inside information. Suddenly we have the upper hand on Scottie. We know what's going on, and he doesn't. It's unusual for a filmmaker to pull a stunt like that -- it's liable to come off as cheating -- but David Cook explains why Hitchcock does it. The revelation has the effect of "destroying suspense in order to concentrate our attention on mood and ambience.... Our perceptual path diverges from Scottie's, and his delusion, which we can no longer share, appears to us increasingly pathetic, hopeless, and doomed." Now that we don't have to puzzle over the mystery along with Scottie, we can take a step back and see how possessive and controlling he is.  What's the big deal: For sheer fun and entertainment, Vertigo is pretty easy to beat. Other Hitchcock films have more surface-level thrills and offer more amusement. Vertigo is the type of movie whose quality increases after you consider its less obvious merits, after you pick apart the psychological weirdness it's suggesting. A second viewing -- when you already know what's going on -- gives you more freedom to marvel at Stewart and Novak's careful, subtle performances. Furthermore, if you accept that Hitchcock is one of the great directors, and if you had to choose one film of his that was "best," there's a certain logic to picking the one that's most reflective of Hitch's style. Of all the Hitchcock films, Vertigo is the Hitchcockiest. Further reading: It's almost impossible to discuss the film's impact without revealing everything that happens in it. So these articles all do. So don't read them until you've seen it. Here are the 1958 reviews from Variety and The New York Times, along with a collection of excerpts from other major reviews. Here are David Ansen's succinct appraisal and Roger Ebert's "Great Movies" essay, both from 1996. The film is discussed in great detail by Tim Dirks at the Film Site. * * * *Eric D. Snider (website) is afraid of widths.

What's the big deal: For sheer fun and entertainment, Vertigo is pretty easy to beat. Other Hitchcock films have more surface-level thrills and offer more amusement. Vertigo is the type of movie whose quality increases after you consider its less obvious merits, after you pick apart the psychological weirdness it's suggesting. A second viewing -- when you already know what's going on -- gives you more freedom to marvel at Stewart and Novak's careful, subtle performances. Furthermore, if you accept that Hitchcock is one of the great directors, and if you had to choose one film of his that was "best," there's a certain logic to picking the one that's most reflective of Hitch's style. Of all the Hitchcock films, Vertigo is the Hitchcockiest. Further reading: It's almost impossible to discuss the film's impact without revealing everything that happens in it. So these articles all do. So don't read them until you've seen it. Here are the 1958 reviews from Variety and The New York Times, along with a collection of excerpts from other major reviews. Here are David Ansen's succinct appraisal and Roger Ebert's "Great Movies" essay, both from 1996. The film is discussed in great detail by Tim Dirks at the Film Site. * * * *Eric D. Snider (website) is afraid of widths.